Opportunities for Digitization in the Humanities – The Etruscan Texts Project

Note - This post was originally published on my Etruscan Studies Blog at the following link on 2024-02-10

In my recent foray into researching the Etruscan language, I came across the the Etruscan Texts Project (ETP), which served as a searchable online repository of Etruscan inscriptions. I found references and links to the website on active UMass Amherst webpages and elsewhere, but the links themselves were dead. With a bit of sleuthing on the Wayback Machine, the most recently indexed working copy of the ETP site I could find was dated to late 2009. Copies indexed from 2011 onward return 404 errors, and reveal that the server hosting the ETP was migrated from Ubuntu to Unix. The linked version of the ETP has entries labelled up to #430, though the jump from ETP 405 to ETP 407 omitted 406, for a total of 429 records.

Details available from the following PDF, sourced from Etruscan News 5 (2006), note that the ETP was in the process of migrating its existing catalog to EpiDoc, an XML format for encoding scholarly and educational editions of ancient documents. It’s not clear to me from the outside what the current state of the project is, but I took it upon myself to experiment with the data available. After downloading a copy of the archived website, I wrote this little Python script using Beautiful Soup, a package for pulling data out of XML and HTML files.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

inputFile = open("/path/to/file.html", "r")

outputFile = open('/path/to/output.csv', 'w')

content = inputFile.read()

soup = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# array to hold list of ETP entries

outputFileEntries = []

for entry in soup.find_all("div", class_="document"):

# string to hold a tentative CSV file single-line for an entry

outputFileLine = ''

for tag in entry:

if tag.name is not None:

formattedTagText = '\t'.join([line.strip() for line in tag.text.split('\n')])

outputFileLine = outputFileLine + "\"" + formattedTagText + "\"" + ', '

outputFileEntries.append(outputFileLine)

for line in outputFileEntries:

outputFile.write(line + "\n")

inputFile.close()

outputFile.close()

This code looks for a div tag specific to the archived ETP page, writing each of its attributes as quoted and comma-separated values, forming lines of a CSV file (available here). Using LibreOffice Calc, I fixed some of the formatting present in the data by default, and used DB Browser for SQLite to convert the CSV file into a SQLite database file (available here). SQLite is a great little database engine that allows embedding a DB in an application as a single file. It may not be a perfect fit for all use-cases, but for surfacing a small amount of catalog data, it’s a nice quick hit for little projects.

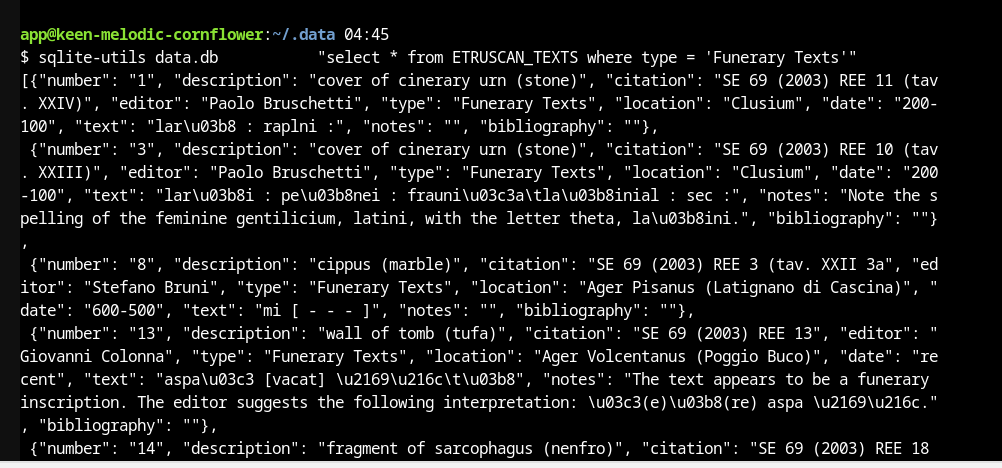

While considering options, I learned of a tool called Datasette, which frames itself as “a tool for exploring and publishing data…aimed at data journalists, museum curators, archivists, local governments, scientists, researchers and anyone else who has data that they wish to share with the world.” I was able to find the easiest way to interact with Datasette, as a Glitch webapp. I forked the app, inserting my own CSV file for the ETP catalog data, and have it running here (Note: as of July 8, 2025, Glitch has decommed all its hosting. I’ll need to move it to my own hosting at some point). The README provides instructions on getting it running. The screenshot below demonstrates running a simple query of the ETP data inside the terminal provided by the app. For those unfamiliar with some of the tooling involved with generating databases or surfacing them via APIs, this is a great toolkit!

Next Steps

I’ve scraped a (possibly very) outdated version of the ETP catalog from the Wayback Machine and migrated it to a database. I’d like to learn more about the need or desire for data like this to remain easily and publicly accessible. It would be straightforward to create a new website that hosts the database, but questions remain about the format of the data, its accuracy, and the best way to enter new inscriptions. Although it remains popular in certain domains, in many cases, XML has been largely obsoleted by JSON, which some may consider an easier format to work with. There may be alternatives to EpiDoc that are more accessible to current tooling. Ultimately, I would love to be involved in any efforts related to digitally cataloging Etruscan inscriptions (or similar needs for other historical languages). If you work in the field and would like to partner with me as an independent researcher or assistant on a part-time basis, please consider getting in touch with me either by comment here or via my email (chaseleinart at proton dot me).